In July 1989, in the heady days of Mikhail Gorbachev's glasnost reforms, a 64-year-old Ukrainian retiree was led to a prison basement in Kyiv to be executed by shooting after a trial that felt like a throwback to another much darker era.

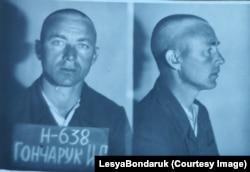

Two years earlier, Ivan Honcharuk had been taken away by Soviet police who pulled up in an unmarked car to his house in a village near Kharkiv.

He was tending rabbits at the time, said historian Lesya Bondaruk, whose book about the case comes out this year. His wife, Anna, had no idea where he was being taken or why.

“The men conducted a search, confiscated documents. They told Ivan to change his clothes and took him away,” Bondaruk told RFE/RL’s Ukrainian Service.

Honcharuk was executed for what he had done 45 years earlier: join the Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA), which was founded in western Ukraine during the Nazi occupation in World War II, and fight against both the Nazis and the Soviet Army.

He is the last UPA member known to have been executed by Soviet authorities.

Shortly before Honcharuk's arrest, Bondaruk said he received an anonymous letter: “Be careful, they are digging around on you because of your past.”

Honcharuk joined the UPA in 1944 after Nazi forces retreated from the Volhynia region where he lived, Bondaruk said.

Honcharuk had already been arrested once before. After the conclusion of the war, Soviet security agencies hunted down Ukrainian nationalists.

He was sentenced to death in a show trial, but his sentence was later commuted to 20 years in Siberia. He was released in 1956 during the political thaw following the death of Soviet leader Josef Stalin.

'The Soviet Empire Was Collapsing'

His rearrest decades later came as political prisoners were being released under Gorbachev’s leadership.

This was also a time of resurgent nationalist feeling in Ukraine and other Soviet republics, which within a few years would achieve independence with the demise of the Soviet Union in 1991.

“The Soviet empire was collapsing. Ukrainian dissidents and human rights activists were active,” said Bondaruk, who works at the Ukrainian Institute of National Memory.

“Perhaps the organizers of the trial thought that they could calm the population, and steps like this court case would help them continue to intimidate people and maintain their position,” she said.

Georgiy Kasianov, head of the Laboratory of International Memory Studies at Lublin University in Poland, said the head of the Ukrainian branch of the KGB at the time, Nikolai Golushko, was known as a hardliner.

“They decided to use [the case] to discredit part of the opposition, because part of the opposition definitely had roots or connections with the UPA veterans, those who were released in the '50s,” he told RFE/RL. “Honcharuk was absolutely from this cohort.”

Allegations Of Nazism

The trial that followed “was a farce,” said Bondaruk. “People in court performed their assigned roles, providing pre-ordered testimony.”

This included a woman who said that Honcharuk was one of four men who killed her father in 1944, when she was 12 years old. The defense lawyer argued that it was unlikely she could recognize Honcharuk so many years later.

“Even within the Soviet justice system it was absolutely against everything,” said Kasianov. “According to Soviet law, he could not be sentenced again for the same crime.”

Borys Plakhtiy was the judge who decided Honcharuk’s sentence, but the case for the death penalty was made by his deputy, Serhiy Kipen.

“Plakhtiy and Kipen sentenced hundreds of people to imprisonment in the gulag…. And then they also denied rehabilitation to these people,” Bondaruk said.

Plakhtiy, who had also sentenced another former UPA member to death years earlier, did not return calls seeking comment. Kipen hung up when RFE/RL called him to ask about the case.

Honcharuk spent two years in Lutsk prison in northwestern Ukraine. Shortly before his execution, he removed his dentures and sent them to his relatives, guessing that his body would not be returned.

He was executed on July 12, 1989, according to official records.

Anna, now 95, still does not know where he was buried.