Crimea's Famed Artek Camp Turns 100, Tainted By Links To Russia Invasion

The Artek summer camp was founded to "educate the citizens of a Socialist society." At the centenary of its founding, the camp's storied history has been overshadowed by its involvement in holding Ukrainian children amid the Russian invasion.

1

A 2009 photo shows a section of the Artek pioneer camp and its statue of Vladimir Lenin on the Black Sea coast of Ukraine's Crimean peninsula.

June 16 will mark a century since the camp was established, beginning a dramatic story of Soviet, Ukrainian, and Russian history.

June 16 will mark a century since the camp was established, beginning a dramatic story of Soviet, Ukrainian, and Russian history.

2

A rare image of the first camp on Artek in 1925, established on Soviet Russia's Crimean peninsula.

The first camp featured four large tents, where children suffering from tuberculosis were housed and encouraged to maximise their time under the sun in the dry climate of Crimea.

The first camp featured four large tents, where children suffering from tuberculosis were housed and encouraged to maximise their time under the sun in the dry climate of Crimea.

3

Exercises on a pebbled beach at Artek in the 1930s.

The camp soon expanded to become a feature of the Soviet Union’s communist youth organization, the Young Pioneers. Places at Artek were set aside each summer for high-performing children, as well as for the offspring of well-connected communist party members.

The camp soon expanded to become a feature of the Soviet Union’s communist youth organization, the Young Pioneers. Places at Artek were set aside each summer for high-performing children, as well as for the offspring of well-connected communist party members.

4

Marshal of the Soviet Union Semyon Budyonny visits the Artek camp in 1946.

Politics soon crept into camp life, as it did elsewhere throughout the fledgling Soviet Union. Matthias Neumann, a history professor who has written extensively on the camp's background, explained to RFE/RL, “Artek served not merely as a recreational site but as a strategic institution for ideological formation.” The academic adds that along with a range of sports and educational programs, politics “was very much in the center of it.”

Politics soon crept into camp life, as it did elsewhere throughout the fledgling Soviet Union. Matthias Neumann, a history professor who has written extensively on the camp's background, explained to RFE/RL, “Artek served not merely as a recreational site but as a strategic institution for ideological formation.” The academic adds that along with a range of sports and educational programs, politics “was very much in the center of it.”

5

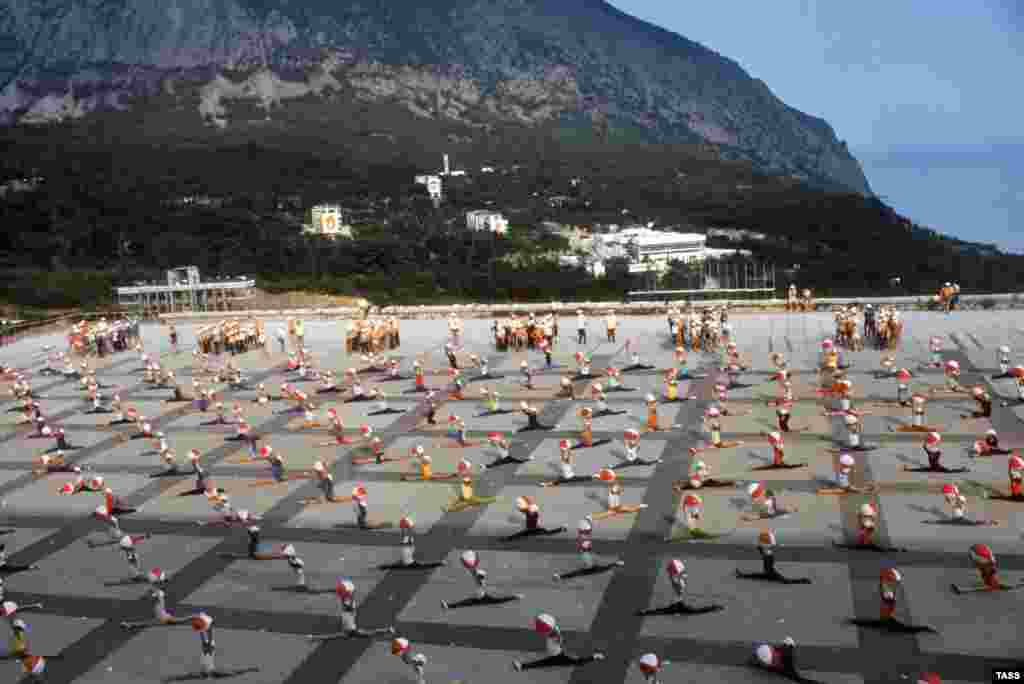

An athletic performance at Artek in the summer of 1977.

Early attendees of the camp were subject to "fiery speeches" from leftist speakers, including German communist Klara Zetkin. More innocent sessions of athletics, theater performances, and hiking trips kept the camp popular for its young clientele.

Early attendees of the camp were subject to "fiery speeches" from leftist speakers, including German communist Klara Zetkin. More innocent sessions of athletics, theater performances, and hiking trips kept the camp popular for its young clientele.

6

Samantha Smith (center right, holding bag) surrounded by young pioneers in Artek in the summer of 1983.

In 1982, American schoolgirl Samantha Smith wrote a letter to Soviet leader Yury Andropov urging him to avoid nuclear war. The letter was published in Pravda, the Soviet Union’s propaganda newspaper, and she was later invited to the U.S.S.R. by Andropov to “find out about our country, meet with your contemporaries, visit an international children's camp -- Artek -- on the sea.”

Some expressed fears Smith was being exploited by the Kremlin. The schoolgirl spent three days at Artek before bidding the camp farewell, saying, “someday, I hope to return. I love you, Artek.”

In 1982, American schoolgirl Samantha Smith wrote a letter to Soviet leader Yury Andropov urging him to avoid nuclear war. The letter was published in Pravda, the Soviet Union’s propaganda newspaper, and she was later invited to the U.S.S.R. by Andropov to “find out about our country, meet with your contemporaries, visit an international children's camp -- Artek -- on the sea.”

Some expressed fears Smith was being exploited by the Kremlin. The schoolgirl spent three days at Artek before bidding the camp farewell, saying, “someday, I hope to return. I love you, Artek.”

7

An August 2005 photo shows, left to right, Ukrainian President Viktor Yushchenko, Georgian President Mikhail Saakashvili, Lithuanian President Valdis Adamkus, and Polish President Aleksander Kwasniewski sharing a meal at Artek.

Following the collapse of the Soviet Union, the camp was inherited by a newly independent Ukraine. But amid the economic turmoil of the 1990s, the site soon fell into disrepair and was later embroiled in scandal over alleged sexual abuse.

Following the collapse of the Soviet Union, the camp was inherited by a newly independent Ukraine. But amid the economic turmoil of the 1990s, the site soon fell into disrepair and was later embroiled in scandal over alleged sexual abuse.

8

A section of the Artek camp photographed in January 2009.

In 2009, Kyiv allocated some 35 million hryvnya (roughly $4.4 million) to refresh the facility.

In 2009, Kyiv allocated some 35 million hryvnya (roughly $4.4 million) to refresh the facility.

9

Children at Artek in May 2015.

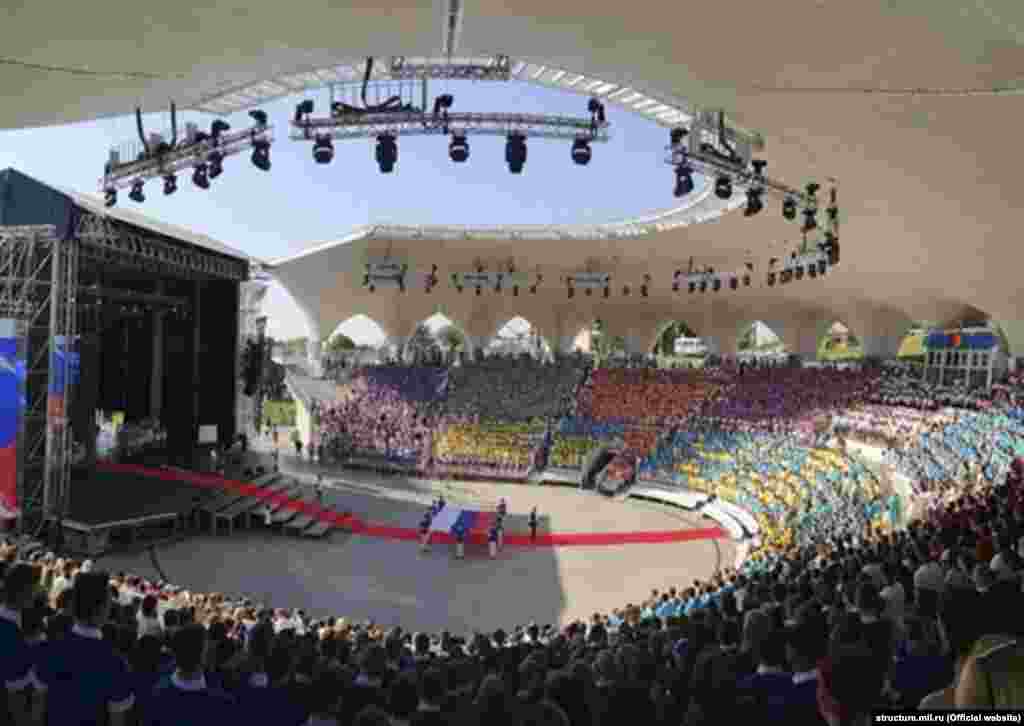

Following the Russian annexation of Crimea in 2014 Russia, Moscow poured millions of dollars into revamping the seaside camp, and it was swiftly reopened with a Kremlin-friendly program.

Neumann told RFE/RL that under Russian control Artek has served as "both as a showpiece of Russian resurgence and as a bridge to the Soviet past," with a view to "shaping young minds, promoting a state-sanctioned image of history, and cultivating loyalty to the Russian state."

Following the Russian annexation of Crimea in 2014 Russia, Moscow poured millions of dollars into revamping the seaside camp, and it was swiftly reopened with a Kremlin-friendly program.

Neumann told RFE/RL that under Russian control Artek has served as "both as a showpiece of Russian resurgence and as a bridge to the Soviet past," with a view to "shaping young minds, promoting a state-sanctioned image of history, and cultivating loyalty to the Russian state."

10

A Russian special forces training session simulating a hostage situation is held on the grounds of the Artek camp in October 2019.

Since the 2014 annexation, some 95 percent of camp attendees have hailed from Russia, although some international guests signed up for summers at Artek, including the children of Syria’s former President Bashar al-Assad.

Since the 2014 annexation, some 95 percent of camp attendees have hailed from Russia, although some international guests signed up for summers at Artek, including the children of Syria’s former President Bashar al-Assad.

11

A performance in a theater in Artek in the summer of 2021.

Following the full-scale Russian invasion in 2022, Artek has become embroiled in one of the darkest aspects of the conflict. Along with several other children’s camps, Artek is known to have hosted Ukrainian children in camps allegedly designed to "Russify" minors, including orphans, caught up in the early Russian advance.

Following the full-scale Russian invasion in 2022, Artek has become embroiled in one of the darkest aspects of the conflict. Along with several other children’s camps, Artek is known to have hosted Ukrainian children in camps allegedly designed to "Russify" minors, including orphans, caught up in the early Russian advance.

12

A section of the camp photographed in 2021.

In 2024, Artek and several people involved in its operation were targeted for sanctions by the EU due to the camp's alleged role in holding Ukrainian children. In many cases, the children "have not been allowed to return home and have been pushed to show their support for Russia," the sanctions report notes.

In 2024, Artek and several people involved in its operation were targeted for sanctions by the EU due to the camp's alleged role in holding Ukrainian children. In many cases, the children "have not been allowed to return home and have been pushed to show their support for Russia," the sanctions report notes.